What is Accessibility?

A General Definition

Accessibility is the practice of making information, activities, and/or environments sensible, meaningful, and usable for as many people as possible.

A common example of accessibility that we have all likely encountered, is in the context of architectural design. Consider the “accessible entrance” to buildings. Railings, ramps, self-operating doors, lifts/elevators, signs, lighting, even the width and height of steps of a staircase all represent accessible design elements. Each function to increase, improve, or eliminate a barrier to a person’s access to a building or structure, and, therefore, that which is housed inside. In some cases, these design features are explicitly for persons with disabilities, but as with accessible design in other contexts, designing for accessibility can significantly enhance user experience for all of us. Think curb cuts used by a parent pushing a stroller, or utilizing a ramp with a small child. In fact, accessible design choices can and should complement or extend the value or function of other design elements (e.g., a handrail or a properly placed and worded sign).

In the case of content accessibility, which is what we specialize in at SeeWriteHear, from the heading structure of a document to its formatting and layout, to the use of visual media and graphical and typographical elements, design choices are applied to increase the usability of documents for the largest number of people as possible.

A Philosophical Definition

In defining and promoting accessibility, it’s important to properly differentiate the problem and purpose of accessibility. Let’s return to architectural design for an example. When a person utilizing a wheelchair for mobility encounters a curb, there clearly exists an instance of in-access (a lack or limitation of access). It’s important to note here, that the wheelchair, or even the need for the wheelchair, is not the problem. The wheelchair is the legitimate means of mobility; the curb is the problem. This may seem obvious, but this distinction is seldom translated to the realm of content accessibility. Rather than viewing improperly formatted content, or poorly written code as the problem, a person’s disability and use of assistive technology is seen by some as the issue to overcome. However, writing, coding, and designing for equitable access is not about solving disability as a problem; it’s about accepting and respecting the solutions and technologies that enable alternate means of access, and then not constructing obstacles to their use.

Accessibility is about Equity

Accessibility is a practice in equitable, responsible design.

Accessibility is about identifying and responding to conditions of in-access, about providing equitable opportunity, regardless of a person’s abilities or circumstances.

Note the emphasis on equity. Understanding the difference between equal and equitable is paramount.

Let’s consider a quick example.

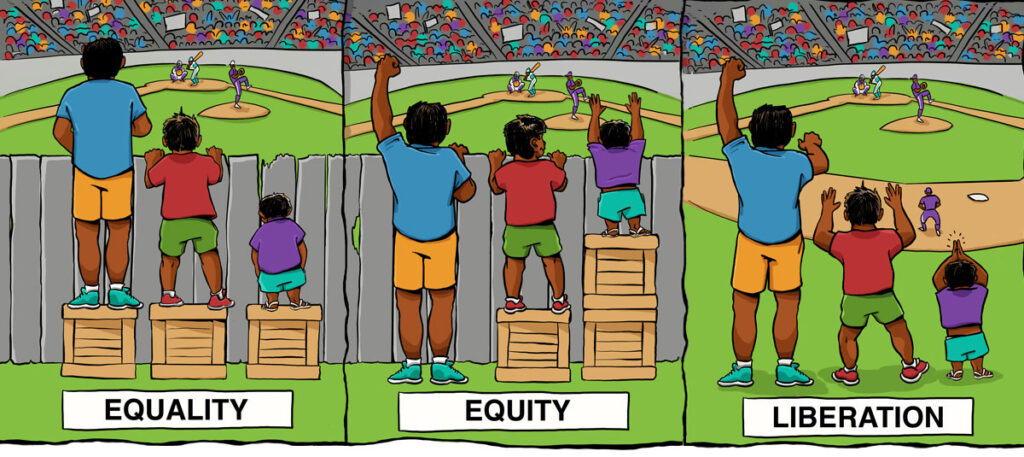

_________________________

[Source: The Center for Story-based Strategy]

In the first panel, three people of varying heights stand on boxes of equal size to watch a baseball game from behind a fence. The third person is not tall enough to see over the fence even with equal access to stand on the same type of box. In this example, we have equality of access determined by equal means (three boxes of the same height). What’s not considered, however, is equality of access determined by the conditions of in-access, i.e., the height of the individual to the height of the fence.

Each of the three people are of a different height, but the conditions of in-access have nothing to do with one’s height in relation to another’s; the conditions of in-access have to do with the height of the fence in relation to the particular individual. Equity is about an equality of access where the means of access (the box) are determined by the particular conditions of in-access (the height of the fence and the height of the individual). I like to think of this distinction as a matter of quality over kind.

The second panel demonstrates an equitable mode of access by determining the means of access (the box) based on the height of each individual in relationship to the height of the fence (again, not to each other). The first individual does not require a box to see over the fence, the second requires one box, and the third requires two boxes.

This is an equitable response because the means of access are equal to the conditions of in-access.

In accessibility we design according to equity not equality. Accessibility is about understanding the particular conditions of in-access facing a person or group. Considering the philosophical definition of accessibility noted above, the most equitable solution to full access by each of the three viewers would be to acknowledge the fence as the problem and remove it, as in the Liberation panel.

Accessibility is about Cultural Practice

Accessibility is a highly subjective, cultural practice, less an objective, technical process. While there are standards and regulations governing much of our decision-making in accessible design, these standards do not always address the biases (social, cultural, economic, technical, etc.) we as accessibility editors might carry forward through our designs, whether intentionally or not. As accessibility editors, we are responsible for not only the products we produce, but the choices we make in our designs and how the world around us shapes our ability to respond ethically and responsibly to issues of access.

Accessibility is about People

It is not about people in general, but about particular people, doing specific things, in identifiable ways.

It is about being able to identify and respond to the ways the design of our content, interfaces, and environments might impede a user’s ability to access, understand, or interact fully and productively.

Accessible design precipitates inclusion and doesn’t create unnecessary barriers to privacy, dignity, and independence for everyone.

Who is an Accessibility User?

Identifying accessibility user communities and the particularity of their needs is a critical process in determining the accessibility of information, content, or processes. And it’s not always an easy or straightforward task.

We traditionally think of accessibility as being about or for people with disabilities. While true, we can sometimes oversimplify the application of the term to the point of unintentionally excluding accessibility users when designing for accessibility.

An example of this might be when we overstate a particular type of disability in defining or locating an accessibility issue. One might continually point to a low-vision user to emphasize the importance of alternative text for graphical objects. While technically correct (people who identify with “low-vision” disabilities may rely on alternative text descriptions), this impulse can sometimes cause us to overlook other members of the accessibility community by our overemphasis. We should remain mindful of this.

An accessibility user is anyone whose access to information, activities, and/or environments are impeded by a temporary, recurring, or permanent condition, including but not limited to,

- Cognitive, Physical Mobility, Auditory, Verbal, or Ocular disabilities

- Age, Language, Culture, Education

- Economic position

- Technological aptitude and access

Everyone, either currently, in the past, or at some future point, will belong to one or more accessibility communities.

And, yet, at the same time, we need to be equally cautious of collapsing the concept into abstracted meaninglessness. By “everyone” we shouldn’t mean all accessibility design must be responsive to all situations in all time, all of the time. That’s not doing anyone any service. Our designs must pay careful and close attention to the intended user and their needs given the identifiable conditions of “in-access.”

Accessibility is about Compliance

Most (not “all”) access issues can be determined via two very helpful frames: usability and compliance.

Compliance refers to following the rules, regulations, or laws of accessibility set forth by organizations, agencies, or communities.

Two commonly referred to compliance standards are Section 508 and WCAG.

Section 508 is a U.S. governmental regulation that covers disability policies and accessibility compliance requirements for government entities, federal employers, and subcontractors and their information and communication technologies.

The Web Accessibility Initiative (WAI)is an international organization that authors accessibility guidelines for web content: Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG). Though primarily focused on accessibility of content on the web, these standards inform how content in other contexts (e.g., MS Office documents, PDF, etc.) should be made accessible.

Accessibility is about Usability

Compliance standards cover a wide range of accessibility concerns, but it’s important to understand that where a document may be compliant, it may not always be usable.

There’s no such thing as 100% accessibility in documents. As accessibility is a condition of user experience, and no two users are alike (i.e., any two users may have varied and even competing needs for accessing information based on their conditions of in-access), we must be particularly mindful of user experience and usability of content based on the specific conditions of in-access for a given user or user community.

Accessibility is about Context

You may be asking, then how do I ensure a document’s accessibility for “all” users if everyone’s needs are so different? In short, you can’t. But if you ensure your file does not (A) break any of the stated compliance rules for your document type; and (B) you’ve applied design decisions that are responsive to the document’s intended user and the conditions of in-access they face, you can be confident that your document is accessible in context.

While accessible design has the potential to improve access for all, there is no guarantee that our design choices will satisfy all situations of in-access. We need to ensure when we examine a document for accessibility, or apply updates to respond to accessibility concerns, that we are carefully considering the conditions of in-access for our intended users. What works in one scenario, may not work for all.

We’re Here to Help

Have you made a commitment to accessibility as a company or agency, but need help in establishing policy or implementing best practices? SeeWriteHear is your partner in all things accessibility related. Connect with us and let’s get started!